By Mohd Hasheem Khan

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a widespread or commonly occurring psychological disorder that affects 1% to 3% of people worldwide. (1) It involves having unwanted thoughts, called obsessions, and feeling the need to repeat certain actions again and again, called compulsions. Obsession are unwanted, repeated thoughts which are hard to control. Compulsions are actions or thoughts that people with OCD perform repeatedly to relieve their anxiety or to prevent something bad from happening.(2) These symptoms takes a lots of patient’s time and make them feel very upset due to which they face difficulty in performing daily activities. People with OCD tend to avoid situations that trigger their obsessive thoughts. (3)

OCD is a diverse condition that is caused by a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors. (4) Most adults feel upset by their unwanted thoughts or actions and they know that they repeat their actions again and again. Children often have difficulty in explaining their unwanted thoughts. In OCD, common fears and actions include fear of germs, excessive cleaning, concern about danger, having disturbing thoughts that lead to mental rituals, and things to be organized which leads to arranging or counting.(5,6) OCD can also present with less common symptoms such as excessive concerned with moral issues, intense jealousy, or a passion for music.(7,8)

The perception of OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder) has changed a lot over time. In the past, people thought it was related to moral problems or even evil spirits. A doctor named Esquirol was the first to describe it medically. Later, Freud, a famous psychologist, called it “obsession neurosis” and suggested that it began due to issues during early childhood development, particularly at the stage when children are learning to control their bowel movements. (9)

CAUSES

The causes of OCD are complex and involve many different factors such as thinking patterns, genes, molecules, environment, and brain function. Studies of twins show that genetics play a big role, with about 48% of the risk coming from genes. (10, 11) But, the genetic effect is reduced to about 35% when maternal influences during pregnancy, such as stress or infection, are considered. (12)OCD in children is more influenced by genetics than in adults. (13) This suggests that OCD that begins in childhood may be a distinct form of the disorder. The results of extensive genetic studies (14, 15) and combined research on specific genes (16) indicates that OCD is affected by multiple genes, each of which has a small effect. Together, these genes contribute to the development of the disorder. Research shows that many different factors can cause OCD in people of all ages. These factors include problems with behavior, brain function, infection, and the immune system, all of which may be linked. (17-22)

Researchers are looking at how genes affect OCD and how these genes relate to other mental and immune problems. (23) One gene being studied is SLC6A4, which influences OCD through genetic changes and processes such as DNA methylation. (24)In addition to the SLC6A4 gene, researchers are also studying other genes related to the serotonin system for their role in OCD. These include the HTR2A, HTR1B and HTR2C genes. (25)

EPIDEMIOLOGY

At first, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) was thought to be quite rare. However, when detailed community surveys were conducted using specific criteria for diagnosing mental disorders, they revealed that OCD is actually one of the most common mental disorders. (26) These studies revealed that OCD contributes significantly to the global burden of disease. (27)

OCD is more common in women than men in the general population. However, in treatment clinics, the numbers of men and women with OCD are approximately equal. OCD affects people of all income levels and is found in both poor and rich countries.

The US National Comorbidity Survey found that about 20% of people with OCD develop symptoms by age 10 or earlier. (28,29) Researchers say OCD usually begins around age 11 and then into early adulthood.(30) Children with OCD are more commonly boys than girls, but not all studies agree. (31,32)

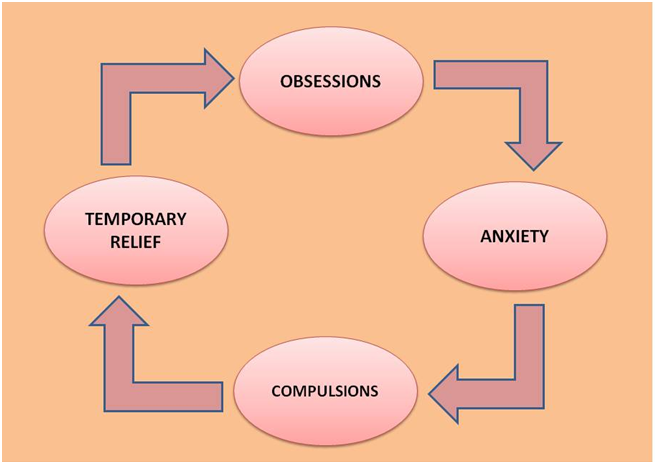

CYCLE OF OCD

There are four stages in OCD cycle:

- OBSESSION

- ANXIETY

- COMPUSION

- TEMPORARY RELIEF

Fig.1.1 Stages of OCD cycle

OBSESSION

OCD thoughts can cover many topics, such as germs or violence, and they are different for everyone. These thoughts can be very disturbing and do not match your own beliefs, especially if you think about them too much or do not understand them.

ANXIETY

OCD thoughts are extremely distressing which causes a significant anxiety and fear. OCD was considered as an anxiety disorder for many years. People with OCD often believe that their intense anxiety indicates that something terrible is happening, and this makes their fear true To get relieve from this anxiety, they feel compelled to perform specific tasks or rituals.

COMPULSIONS

Compulsions are the actions or thoughts that you used to reduce the anxiety from OCD. They can be things you do physically or just in your mind. For example, if you’re worried that your thought may cause a disaster, you may feel the need to mentally remove the thought many times to keep everyone safe.

TEMPORARY RELIEF

After meeting your obligations, you may feel better for a while, but it won’t last for a long time. OCD will constantly add new worries in your mind, this cycle will continue as long as you are afraid and try to avoid these thoughts.

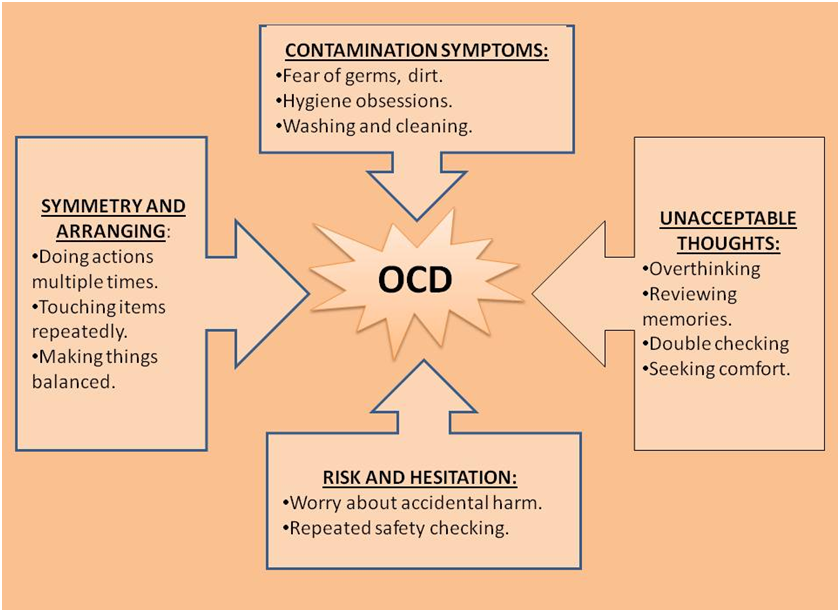

Categories of OCD symptoms:

- Symmetry and arranging

- Contamination symptoms

- Unacceptable thoughts

- Risk and hesitation

FIG.1.2 Types of OCD symptoms

TREATMENT OF OCD

Many individuals can get benefit from treatment, including those which have severe OCD. Healthcare providers use medications, psychological therapy, or a combination of the two to treat OCD. A mental health professional can help you choose the most appropriate treatment and explain the advantages and disadvantages of each option.

Psychological therapy

1. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

It is a proven and first-choice treatment for OCD. It helps by changing the harmful thoughts and behaviors of the patients. This therapy focuses on rewiring the way that person thinks and acts. CBT aims to replace the unhealthy thoughts and behavior patterns with the healthier ones.

In CBT, exposure and response prevention (ERP) method is very successful approach to treat OCD. It involves exposing patients to things that causes anxiety and they are taught that they should not act on their compulsive behaviors. (33)

PHARMACOTHERAPY

- Serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Selective Serotonin reuptake Inhibiters (SSRIs): These are the best medicine to treat OCD because they are highly effective and show very less side effects.

In 1989, Goodman and his team discovered that fluvoxamine was very effective in managing OCD. (34) After that, over 20 studies proved that SSRIs are more effective in the treatment of OCD. (35, 36)

Side effects of SSRIs are:

- Weight gain

- Sleep disturbance

- Nausea

- Low libido

- Diarrhea

- Tricyclic antidepressants

CLOMIPRAMINE: It was very useful medicine in the 1980s, which is used to treat depression. The effectiveness of clomipramine is similar to SSRIs, but it shows more side effects like sedation, weight gain, etc. which makes it less suitable for the treatment.(37,38) The active metabolite of clomipramine is desmethylclomipramine. Clomipramine affects serotonin and Desmethylclomipramine affects the norepinephrine neurotransmitter. It is metabolized in liver with the help of CYP1A2 enzyme. People who have low level of CYP1A2 enzyme they need small or low dose of clomipramine. It is not allowed to prescribed Clomipramine in combination with MAO inhibitors or CYP 450 2D6 because it will show some toxic symptoms like arrhythmia, low blood pressure, seizures, etc.

Sometimes Clomipramine is also used in the treatment of many other diseases which is not officially approved like:

- Depression (39)

- Sudden muscle weakness (40)

- Anxiety (41)

- Neuralgia (42)

- Premature or early ejaculation (43)

- Panic attacks (44)

- Sleep disorder (40)

Side effects of antidepressants are:

- Sweating

- Dry mouth

- Tachycardia

- Headache

- Nausea

- Antipsychotics

Antipsychotics and other classes of drugs are recommended by the doctors to OCD patients when antidepressant does not show their actions properly.

| S. No | Category | Name of Drug |

| 1 | Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRIs) | Fluoxetine |

| 2 | Urine (40-45%), Feces (40-45%) | Sertaline |

| 3 | Tricyclic Anti Depressant | Citalopram |

| 4 | Antipsychotics | Venlafaxine |

| Clomipramine | ||

| Aripiprazole | ||

| Risperidone |

| Bio -Availability | Excretion | Marketed Formulation |

| 60-80% | Urine (80%) Feces (15%) | FLUSAG-20 PROZAC-20 |

| 44% | Urine (40-45%), Feces (40-45%) | SEROLIX-25 ZOLOFT |

| 80% | Mostly in urine | CELEXA SILAM-40 |

| 42±15% | Urine (87%) | EFFEXOR XR |

| ~50% | Renal (51-60%), Feces (24-32%) | ANAFRANIL CLOMER-25 |

| 87% | Urine (27%) Feces (60%) | MORIP-5 ABILIFY |

| 70% | Urine (70%) Feces (14%) | RASOMAX RISPERDAL |

DEEP BRAIN STIMULATION (DBS)

It is a flexible and reversible method which is used in the treatment of severe OCD. It shows action upto 40 to 70% of the patients who get this treatment. In this procedure, an electrode is placed in the deep brain by surgical method, then the electrode stimulates the nearby area of the brain. DBS target only some specific regions like the anterior limb of the internal capsule and the ventral striatum. It is a safe and impactful treatment authorized by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (1,2)

OCD REFERENCE

1. Zai G, Barta C, Cath D, Eapen V, Geller D, Grünblatt E. New insights and perspectives on the genetics of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Genet. 2019 Oct;29(5):142-151.[PubMed]

2. Stein DJ, Costa DLC, Lochner C, Miguel EC, Reddy YCJ, Shavitt RG, van den Heuvel OA, Simpson HB. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019 Aug 01;5(1):52.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

3. Strom NI, Soda T, Mathews CA, Davis LK. A dimensional perspective on the genetics of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2021 Jul 21;11(1):401. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

4. Blanco-Vieira T, Radua J, Marcelino L, Bloch M, Mataix-Cols D, do Rosário MC. The genetic epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2023 Jun 28;13(1):230. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

5. Mataix-Cols D, Rosario-Campos MC, Leckman JF. A multidimensional model of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005 Feb;162(2):228-38. [PubMed]

6. Bloch MH, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Rosario MC, Pittenger C, Leckman JF. Meta-analysis of the symptom structure of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 Dec;165(12):1532-42. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

7. Taylor S, McKay D, Miguel EC, De Mathis MA, Andrade C, Ahuja N, Sookman D, Kwon JS, Huh MJ, Riemann BC, Cottraux J, O’Connor K, Hale LR, Abramowitz JS, Fontenelle LF, Storch EA. Musical obsessions: a comprehensive review of neglected clinical phenomena. J Anxiety Disord. 2014 Aug;28(6):580-9. [PubMed]

8. Greenberg D, Huppert JD. Scrupulosity: a unique subtype of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010 Aug;12(4):282-9. [PubMed]

9. Fornaro M, Gabrielli F, Albano C, Fornaro S, Rizzato S, Mattei C, Solano P, Vinciguerra V, Fornaro P. Obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders: a comprehensive survey. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2009 May 18;8:13. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

10. Fernandez TV, Leckman JF, Pittenger C. Genetic susceptibility in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;148:767-781. [PubMed]

11. Goodman WK, Storch EA, Sheth SA. Harmonizing the Neurobiology and Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2021 Jan 01;178(1):17-29. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

12. Mahjani B, Klei L, Hultman CM, Larsson H, Devlin B, Buxbaum JD, Sandin S, Grice DE. Maternal Effects as Causes of Risk for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2020 Jun 15;87(12):1045-1051. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

13. van Grootheest DS, Cath DC, Beekman AT, et al.. Twin studies on obsessive–compulsive disorder: a review. Twin Res Hum Genet 2005;8:450–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Stewart SE, Yu D, Scharf JM, et al.. Genome-wide association study of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2013;18:788–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Mattheisen M, Samuels JF, Wang Y, et al.. Genome-wide association study in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from the OCGAS. Mol Psychiatry 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Taylor S. Molecular genetics of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a comprehensive meta-analysis of genetic association studies. Mol Psychiatry 2013;18:799–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Rapoport JL. Childhood-onset obsessive compulsive disorder.Psychiatr Clin North Am 1992;15:767-75. 10.1016/S0193-953X(18)30207-7 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Nazeer A, Calles JL. Anxiety disorders. In: Greydanus DE, Patel DR, Omar HA, et al. editors. Adolescent Medicine: Pharmacotherapeutics in General, Mental and Sexual Health. Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter, 2012:255-67. [Google Scholar]

19. Patel DR, Brown KA, Greydanus DE. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. In: Greydanus DE, Calles JL, Nazeer A, et al. editors. Clinical Aspects of Psychopharmacology in Childhood and Adolescence. Second Edition. NY: Nova Science Publishers, 2017:117-27. [Google Scholar]

20. Boydston L, French WP, Varley CK. Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. In: Greydanus DE, Calles JL, Nazeer A, et al. editors. Behavioral Pediatrics. New York: Nova Science Publishers, 2015:277-87. [Google Scholar]

21. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

22. Drubach DA. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder.Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2015;21:783-8. 10.1212/01.CON.0000466666.12779.07 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar].

23. Tylee DS, Sun J, Hess JL, et al. Genetic correlations among psychiatric and immune-related phenotypes based on genome-wide association data.Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2018;177:641-57. 10.1002/ajmg.b.32652 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. 84. Grünblatt E, Marinova Z, Roth A, et al.Combining genetic and epigenetic parameters of the serotonin transporter gene in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Psychiatr Res 2018;96:209-17. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.10.010 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Sinopoli VM, Burton CL, Kronenberg S, et al.A review of the role of serotonin system genes in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2017;80:372-81. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.05.029 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Karno M The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in five US communities. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 45, 1094 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Baxter AJ, Vos T, Scott KM, Ferrari AJ & Whiteford HA The global burden of anxiety disorders in 2010. Psychol. Med 44, 2363–2374 (2014). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]This systematic review provides the foundation for estimations of the global burden of anxiety and related disorders.

28. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Delorme R, Golmard JL, Chabane N, et al. Admixture analysis of age at onset in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychol Med. 2005;35:237–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Geller D, Biederman J, Jones J, et al. Is juvenile obsessive-compulsive disorder a developmental subtype of the disorder? A review of the pediatric literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:420–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Chabane N, Delorme R, Millet B, Mouren MC, Leboyer M, Pauls D. Early-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder: a subgroup with a specific clinical and familial pattern? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:881–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Hirschtritt ME, Bloch MH, Mathews CA. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA. 2017 Apr 04;317(13):1358-1367.

34. Goodman WK, et al. Efficacy of fluvoxamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder. A double-blind comparison with placebo. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(1):36–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Soomro GM. Obsessive compulsive disorder. Clin Evid (Online) 2012;2012 [Google Scholar]

36. Soomro GM, et al. Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) versus placebo for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD001765. [PMC free article][PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Grant JE (August 2014). “Clinical practice: Obsessive-compulsive disorder”. The New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (7): 646–653.

38. Insel TR, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. A double-blind trial of clomipramine and clorgyline. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40(6):605–612.[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Meyer JH, Wilson AA, Ginovart N, Goulding V, Hussey D, Hood K, Houle S. Occupancy of serotonin transporters by paroxetine and citalopram during treatment of depression: a [(11)C]DASB PET imaging study. Am J Psychiatry. 2001 Nov;158(11):1843-9. [PubMed]

40. Palmer NR, Stuckey BG. Premature ejaculation: a clinical update. Med J Aust. 2008 Jun 02;188(11):662-6. [PubMed]

41. Montgomery SA, Baldwin DS, Blier P, Fineberg NA, Kasper S, Lader M, Lam RW, Lépine JP, Möller HJ, Nutt DJ, Rouillon F, Schatzberg AF, Thase ME. Which antidepressants have demonstrated superior efficacy? A review of the evidence. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007 Nov;22(6):323-9. [PubMed]

42. Hollander E, Allen A, Kwon J, Aronowitz B, Schmeidler J, Wong C, Simeon D. Clomipramine vs desipramine crossover trial in body dysmorphic disorder: selective efficacy of a serotonin reuptake inhibitor in imagined ugliness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999 Nov;56(11):1033-9. [PubMed]

43. Rothbart R, Amos T, Siegfried N, Ipser JC, Fineberg N, Chamberlain SR, Stein DJ. Pharmacotherapy for trichotillomania. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Nov 08;(11):CD007662. [PubMed]

44. Caldwell PH, Sureshkumar P, Wong WC. Tricyclic and related drugs for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Jan 20;2016(1):CD002117. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

1 thought on “Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)”

I appreciate your insights on mental health. It’s so important to talk openly about these issues!